Cropping determines the dimensions and boundaries of the final image. In addition, cropping ultimately determines the artistic and aesthetic placement of the central focus of any image.

Cropping occurs twice during the creation of a photograph:

- The first crop is performed in the camera as the photographer composes the picture in the viewfinder. The photographer decides at this time the limits of the scene that will be contained within the 4 borders of the picture as well as the elements (objects) that will be captured.

- The second crop takes place in the iDarkroom. Digital imaging programs contain cropping tools that allow the photographer to perform a final technical and artistic adjustment to define the dimensions and element contents of the final image.

- Aesthetically, cropping the image in the camera forces the serious photographer to focus on the rules of good composition and to mentally visualize the final image.

- Technically, cropping in the camera produces a digital file that requires less cropping in the iDarkroom which interprets to sharper final prints. Excessive digital cropping and/or enlarging reduces the resolution and, consequently, the quality of the final photograph.

Because of the importance of cropping to photography, virtually every digital imaging program offers tools to perform this function. I will use cropping examples with Adobe's Lightroom and Photoshop. Most imaging programs will offer a tool with similar functionality.

This is my sample picture for walking through Lightroom and Photoshop's cropping functions. To match the pre-visualized image of this outstanding photographer (me), some cropping refinement is required.

Shown above is the same image with the areas to be eliminated shaded in brown. Notice: I am not concerned about the size of the final image at this stage. I am only concerned with the contents of the image appearing within the borders of the final print.

Cropping Screen with the Lightroom's Develop Module

Lightroom's cropping tool (red box above) is available from the program's Develop Module. Clicking on this tool reveals the window shown above. A free-hand cropping icon (shown in green) is available for a click-and-drag cropping. Or, handles that appear on each corner and the center of each side can be clicked-and-dragged to a new location. (Normally, I use the six handles to define the cropped area.)

An additional convenience provided in Lightroom is the inclusion of "rule of thirds" indicators. Faint grid lines that divide the picture into thirds horizontally and vertically are overlaid on the picture. The four intersections of these grid lines (shown in blue) are the "rule of thirds" points for subject placement. The locations of these points change dynamically as the crop (border lines) is moved -- nice touch for beginning and advanced photographers alike.

Here is a closer view of the Lightroom screen with the crop lines positioned. The image areas in dark gray will be eliminated (cropped) from the final digital picture. By pushing the "enter" key, the crop will be performed, and the final image appears.

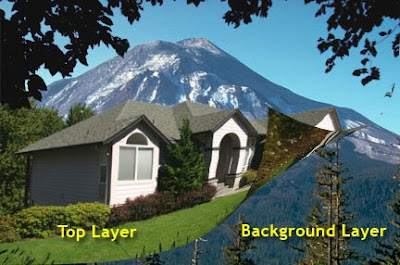

Remember from our previous discussion about the non-destructive editing features of programs like Lightroom and Apple's Aperture, the original digital file is NOT being altered. The information about the crop just performed will be included along with any other corrections in a separate file and applied to this image whenever it is displayed on the monitor. The original uncropped and unaltered file is ALWAYS retrievable.

Let's compare this cropping technique to that used by Photoshop and many similar programs.

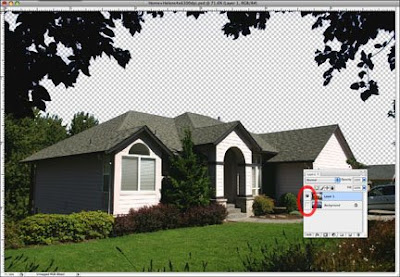

In Photoshop, the cropping tool is always present on the left-hand tool bar as shown in the red circle above. This icon has become almost universal and looks similar in other editing programs. Clicking on this tool activates the cropping function.

In the picture above, the crop tool (a click-and-drag functioning tool) has been positioned as indicated by the "marching ants" marque. After releasing the mouse button, the area to be "cropped out" will be shown in dark gray (above). Notice, much like Lightroom, that six positioning handles also appear when the mouse button is released (red circles above). Using these handles allows for final precision positioning of the borders of the crop. Hitting the "return" or "enter" key completes the cropping function.

Remember, Photoshop and similar editing programs work on a destructive editing process. In other words, the original file HAS been altered. So, perform a "SAVE AS" command and use a new file name NOW. This will ensure that the original file will NOT be overwritten and destroyed.

Simultaneous Cropping and Sizing

It is possible to perform cropping and image re-sizing at the same time with the cropping tool. Having this capability allows the photographer to specify the desired specific print size and print resolution while performing the cropping.

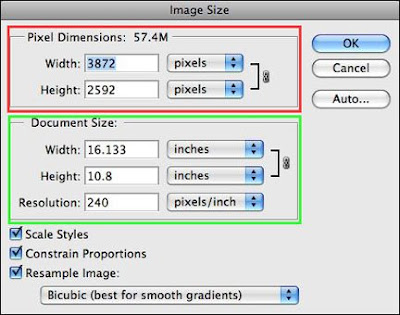

This picture requires cropping to correctly position the subject. In addition, I know that a final print with the dimensions of 10" x 8" at 240 ppi is required. With Photoshop's cropping tool, I can perform both operations at once.

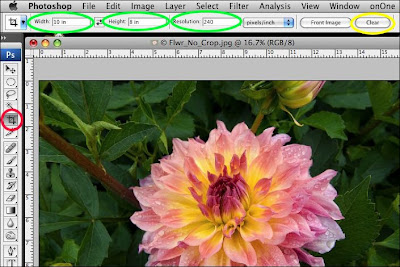

Photoshop's cropping and resizing functions

With the cropping tool selected (red circle above), I can type in specific dimensional attributes in the width, height and resolution boxes (shown within the green circles above). In this case, a width of 10", a height of 8" and a resolution of 240 ppi are typed into the boxes.

Caution: When you don't want to automatically re-size an image to specific dimensions or PPI resolution, these boxes must be blank. Using the "Clear" button (yellow circle above), will erase any specified sizing in the width, length and resolution boxes.

Now, as the click-and-drag is performed with the mouse, the crop is constrained to the proportions of 8"x10". Any crop can be accommodated when you perform this operation, as long as it conforms to the proportion of 8 by 10. The crop and re-sizing is completed by hitting the "return" or "enter" key.

Check the properties of this image and you will discover that the new cropped image is 8 inches by 10 inches with a resolution of 240 ppi. Remember to save this file under a new file name to prevent overwriting the original file. Most modern image editing programs incorporate this time-saving feature in their cropping tools.

You will find that the cropping tool is one of your best friends and most utilized tools. Because of the frequency of use, cropping will soon become second nature.