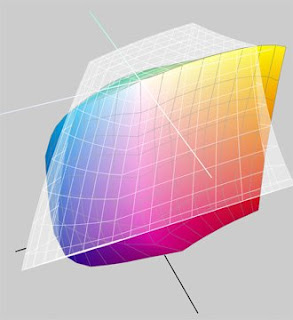

In the iDarkroom there are several “worlds” of color. It's these multiple worlds of color that cause the confusion and misconceptions about reality that plague photographers. The color worlds that most immediately impact the results of your photography are represented by the globes below:

This globe illustrates all the colors (color space) the human eye is capable of recognizing.

This globe shows the color space that your computer monitor is able to display.

Finally, this globe represents the color space that a typical color photographic ink jet printer can reproduce.

These globes contain all the colors that our eyes, computer monitor and color printer can recognize or reproduce. At first glance, the natural tendency is to believe that all three worlds are the same, and that each device recognizes and reproduces the same colors.

It's not going to be that easy. In reality, the size of these three color worlds is significantly different. Although simplistic, the picture below is a more understandable representation of the volume of colors in each world:

As this graphic illustrates, neither a computer monitor nor a photo printer have the color range of the human eye. In fact, the photo printer has a color world that’s smaller than the computer display. In photo jargon, these worlds are known as color gamuts. Each input and output device in a photographic system has its own color gamut.

So, although all three color gamuts contain red (for example), the "Human Eye" is capable of recognizing more "shades" and "densities" of red than either the monitor or printer are able to reproduce. It doesn't take a rocket scientist to see the photographer's dilemma. "If the last component in the photographic system (the printer) is not capable of reproducing all the colors that my eye can see, then how can any final picture be true to reality?" The short answer is: The final picture is rarely a perfect match to reality.

But, by understanding these color space differences and accepting some compromises, as well as taking the necessary steps to calibrate and synchronize all the devices in the entire process, incredible images can be created. (Remember the airplane monitors: they were all trying to display the same images in the same color space, but they were not calibrated or synchronized. As a result, they all displayed color differently.)

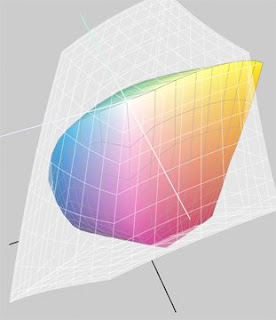

Let’s start by giving you a look at the real gamuts in our photographic system. In this example, I have selected the Adobe RGB space option on my digital camera. Shown below are all the colors (or gamut) of this color space. All pictures taken with this camera will be translated to fit within this Adobe color space:

The Adobe RGB (1998) color space is displayed here using Apple Computer's Color Synch® utility program that is included on Apple Macintosh® computers.

Although no industry standard has been declared, Adobe RGB (1998)® is probably the most common and one of the larger color spaces commonly used in photographic applications. I recommend using this space as your starting point for learning the ins and outs of color management.

Now we know the color space of our camera (Adobe RGB 1998). How do monitors and printers relate to this color space? The Color Synch® utility included with Macintosh® computers provides a visual comparison of these color spaces. Take a moment to study the 4 comparisons shown below. The problem of color matching and color management becomes immediately apparent.

I am using a Hewlett Packard Photosmart Pro B9180 13" printer in these color space comparisons. Similar graphs would be seen with comparable printers from other companies like Epson and Canon.

Knowing that these differences in color spaces between the components of your photographic system exist is the first step towards managing your color environment and achieving the results you are expecting.

A) Apple iMac Monitor Color space compared to the Adobe RGB color space (white wire frame). Notice the Monitor's Color Space fits within the Adobe RGB space and is not capable of displaying the entire Adobe RGB space.

B) HP’s Pro B9180 printer color space compared to the Adobe RGB color space (white wire frame graph). The printer is not capable of printing all the colors contained in the Adobe RGB color space. In addition, the printer is capable of producing colors that are outside the Adobe RGB space (see yellow and orange segments that extend beyond the Adobe space.)

C) HP’s Pro B9180 printer color space compared to the iMAC monitor color space (white wire frame graph). The differences are again apparent between these two devices. Each space contains colors that the other cannot replicate.

D) Finally, HP’s Pro B9180 printer color space compared to the Adobe RGB color space. This comparison is identical to the graphic in figure B above. The difference is that the top image is the printer’s color space when using glossy paper while this image is the printer’s color space when printing on a matte fine-art paper. Yes, to add yet another variable, the paper you use in your printer makes a difference as well.

And, calibration is where the next post will begin. Hang in there. It will all come together, and you'll be the master of your iDarkroom domain.

Note: Apple Macintosh® computers and Apple Computer's Color Synch® utility were used in this discussion for illustration purposes. These color space issues are identical on PCs as well.